If Dostoyevski Had Instagram

Image taken from Mari Andrews on Instagram (@bymariandrews)

Recently, as I shuttled my new babies down to Boston for a checkup, I listened to a podcast of writers discuss how social media is changing us, changing the way we live. One of the writers on the podcast was Dani Shapiro, whose memoir Slow Motion, about her parents’ car crash and her father’s death I happened to be reading at that time. She was talking about another writer friend whose parent was in their final days, and who shared on Facebook about her parent’s flame slowing being extinguished. Shapiro was struck by how, as her own father was dying twenty years earlier, there was no social media. She wondered if she had Facebook on her phone when she hopped on the plane to go home after she learned of their car crash, would she have posted about it? The tension of all of her feelings around these events having no release is what prompted her to write Slow Motion. If she had posted about these events, would she still have written the book?

It was fascinating to hear writers analyze how social media is changing us, especially because most of the writers I admire are not on Instagram, or are on Instagram and have 350 followers because they are busy writing and not building an online presence. They give me perspective for what is truly meaningful in the sea of voices we are presented with, because I want to be more like them and less like the people who are Insta-famous. What would it be like if C. S. Lewis or Dostoyevski had an Instagram feed? Would they be so busy posting that we would not have Surprised by Joy or A Grief Observed? Or The Brothers Karamazov?

Writers today are caught in the conundrum of using their writing time to both actually write and to build up a following on social media. Yet good writing comes from retreating, withdrawing, reflecting. And writers are cautioned about what they are consuming while trying to be productive. Stephen King famously called television the ‘glass teat’ and warned his audience to wean themselves off if they wanted to write well. Reading good books is the conduit to good writing, which only happens if we put down our phone and pick up a tome.

While writing and food blogging brought me into social media, motherhood is what has forged community there. I am part of a unique generation that will have mothered both before and after social media took hold. Ten years ago, when my oldest was almost two, we had a flip phone to make phone calls and a flip camera to record videos of our kids. By the time I had my third child, I got a smart phone and had just joined Facebook. And my fourth son’s birth ushered in both Instagram and Snapchat, which was then ushered out by Instagram Stories. When my children were small, being a mother was filled with tremendous experiences, but it didn’t occur to me to post these on Facebook because I didn’t think my old co-workers and high school friends wanted to hear about my mastitis or sleep deprivation. Motherhood was still intensely personal, and private, and isolating. But then people started to share these moments, these experiences on Instagram, and these shared experiences forged something powerful.

There is no question that social media has made the most isolating years of motherhood now a time of community and tribe building. With my last pregnancy, people were praying and congratulating us through the power of hashtags and online communities. My pre-social media births that went undocumented, that garnered no likes or any attention at all were the highlights of my life, seen or unseen. But there is power in ameliorating the feeling that you are all alone in the hopes and fears that motherhood brings. As I sit for hours now feeding babies, I can still find some connection with people and ideas. I can be entertained by witty humor. And in rocky times of parenting, you can find the power of shared experience. When our son with Down syndrome was rushed to the hospital and we discovered he had Hirschsprung’s Disease, through the hashtag #hirschsprungs I had found within hours another mother in Canada who had twins, one with Down syndrome and Hirschsprung’s. “You are literally the only other person in my situation,” she wrote. We would never have found each other, in the narrowest of all Venn Diagram possibilities, without Instagram. Through social media I found a community that prepared me for horrible diaper rashes and multiple doctors appointments and life with a g-tube. If we were to quantify the power of social media as a type of ‘knowing’ about experiences it’s enormous. I was able to know what to expect exponentially faster than if I had been in that situation ten years earlier.

But there is another type of knowing that is challenged by how social media impacts us. One writer lamented the tendency to always want to find the ‘narrative arc’ of their experiences, the framework to wrap things in that would make for good storytelling, instead of truly living their life in all of its immediacy and authenticity. This I think is the same danger that Instagram does to us. If we spend too much of our conscious attention on thinking of how that moment could be consumed instead of lived, how framing the photo, finding the right light, the right composition, instead of being with the subjects of the photo themselves, we lose out on what the immediate experience is offering up to us – the scent of morning rain, the laughter of our children, the song of the birds in the tree outside your window. And that of course is where we find true joy. Often it is that real joy we are trying to share, but it is healthy to keep checking that the sharing doesn’t eclipse the joy.

And there is something appealing to our creative souls for looking for the photo in the first place, for wanting to tell the story of a moment. Especially the heartwarming moments of motherhood. The human urge to keep an account is timeless. And for many people, the value of social media is keeping a record of our lives that might otherwise pass in a blur. The size of our babies, the height of our teens, the homes we live in. Some people argue that we spend too much time on social media, and while that may be true, long before we had it, people spent time connecting and recording. A hundred years ago, the habit of writing letters, diaries, and journals was commonplace. And large parts of people’s days were spent being social, perhaps even more than ours as we post on Instagram.

But that may be the problem. We are Insta-social. If we are not careful, we can spend time on being social but only a few seconds at a time, instead of, say, an afternoon on a Sunday family meal, or a half hour writing a letter. It is more convenient, but it is at a proximity that is much further away, in tiny squares, at lightning speed. And the result is that we are often just hearing noise, or getting quickly nudged by others, instead of being truly touched. For me, what ends up feeling like ‘noise’ is those who present a very superficial and manufactured self. What ends up truly touching me is when people share a real, authentic human experience. Support, connection, and collaboration do grow out of social media. We can and should be a source of positivity and caring wherever we are, social media especially. But we can discern those who are letting a real self, and not shades of their ego, come through.

I came at Instagram as a writer first, and for me, success in this craft is how well you capture truth. The opposite is often the case on IG – it is how well you capture what is desirable. Many people view success on IG as popularity, even if you are getting the attention by totally fabricated and untrue images. There are some Instagram accounts that have huge followings and the majority of the pictures are of them lying in bed with their children, eyes closed, seemingly asleep. Who is the person that climbed up and hovered over them to take the picture? I wondered. I asked in the comments. Their husband. I can’t imagine my real-life husband having the time to hover over our bed to take a picture, to arrange the covers just so, while I pretend to sleep. And then doing it again fifty other times.

The tricky part, the part that confuses the real knowing, is that they appear to be reflecting in the post. Under the picture of the husband staging the moment of sleep for his wife and children includes something like ‘I’m never letting go’ and then the hashtags #soblessed, #heartsfull. It’s not really reflecting at all if it is premeditated or staged. It’s definitely not if there are any brands being tagged. And that’s ok, if we are not confusing what is being shared. Obviously, some accounts become what magazines were – glossy representations of perfect homes, families and houses, with plenty of ads. My guess is if you never liked those kind of magazines, you won’t like those types of accounts either. But when we see the number of people that follow such fabricated images, we are left scratching our heads, wondering what our society values.

What is vastly different from a hundred years ago, or even from reading magazines, is the rate at which we consume other people’s experiences. This is I think the variable that is changing us the most. Having already ‘known’ about an experience by consuming it from someone else’s social media content, we can be in danger of not giving ourselves the time and space to have our own experiences, to reflect in a slow and meaningful way. The surprise and joy of a new pregnancy might dissipate as it gives way to thoughts about how to announce it on social media. It’s wonderful to share a pregnancy announcement. But it is also a special thing for you and your family to be the only ones that know, and to process the news, and then share it in an authentic way. The change in seasons now can be perceived more from a shift in color scheme on someone’s feed then actually going out and taking a walk, and must be shared as soon as we drink our first PSL, which we bought because someone else just posted one yesterday. A homogeny of experience arises, and the complexity and richness and wonder of life is lost as we all repeat and regurgitate what we are taking in.

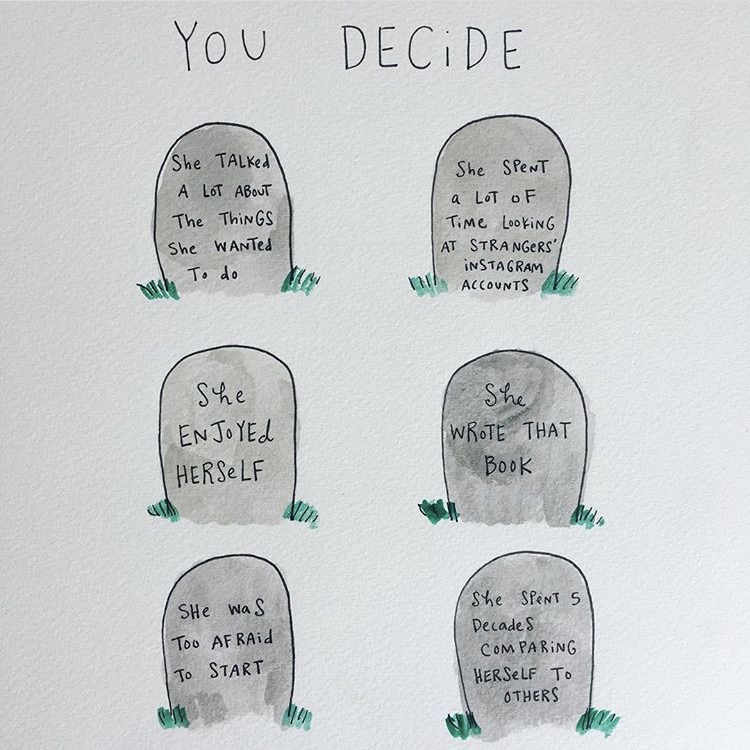

I think about the question that Dani Shapiro posed – does sharing these moments dissipate an innate tension in our lives that might propel us to greater things? Would we make more and better art if we weren’t curating a feed? This is hard to say, since many people build their art though Instagram. But for sure, there are less tangible evidences of the human urge to create – less buildings, less art to put in buildings, less art to hold in our hands – as we pour more and more of our artistic impulses into the digital sphere.

These questions press on me most as a mother. How will I plan to teach my kids about social media? Right now, their consumption of it consists of YouTube videos (Heaven help us). But there are plenty of teaching moments in just this arena. How is it that a girl’s first time making slime has 3.5 million views? Who is buying all these toys these kids are opening? Like most parents, I am faced with answering this: What degree of participation should I let my kids have in social media? When she gets older, should I let my daughter have her own YouTube Channel if she desires to participate and share in this arena? The answer for now is no but I have to admit I don’t fully know what the right answer is down the road. There is plenty of leadership, initiative, knowledge, public speaking skills, and entertainment in the few videos she has recorded on my phone in the event that I might change my mind and let her share them. But besides safety, I got back to Dani Shapiro’s pressing question: what is not being created because we are sharing so much instantly? What will grow in my daughter and take root if she is forced to stay isolated while she develops her skills and interests? My instincts tell me good things.

The one thing that is clear in all of this change is that we are getting used to not being alone. Now we are all in each other’s doctor appointments, living rooms, date nights and kitchens. This isn’t all bad. We are less isolated, and some might argue, more engaged, more alive. But it does mean we have to try harder to find ways to be alone, to intentionally carve out space in our day for silence, for quiet. To see what takes root when no one is looking.

So the antidote may be this, to just sit quietly with ourselves and with our God. He will give us everything we need, so that when we turn to social media, we are already filled up. We don’t come at it hungry. In already getting all the approval, attention and love He has waiting for us, we don’t look for these from others. Maybe a way to determine helpful versus harmful consumption is think about the end goal. If your end goal is attention, then perhaps you need to be cautious about your social media use. But if your end goal is to authentically create art, love your family, be healthy, mourn your loved one, or grow spiritually, and you share your journey towards getting there, it seems there is value, and true knowing, and community to be found.

We are all fumbling around what social media means to us, and I was comforted to hear writers I admire admit they are thinking it through for themselves. Perhaps Dostoyevski would have fumbled too. But I like to believe he would have sought out the quiet to think, to journal, to write, to have a meal with real conversation, to pray. These are the source of true reflecting, and the meaningful knowledge that it brings. Because no matter how many likes the shot of your PSL or the photo of you sleeping with your cherubic children gets, only this really satisfies.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!